-40%

TRAJAN DECIUS Sestertius Rare Ancient Roman Coin Dacia w draco standard i46698

$ 126.08

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

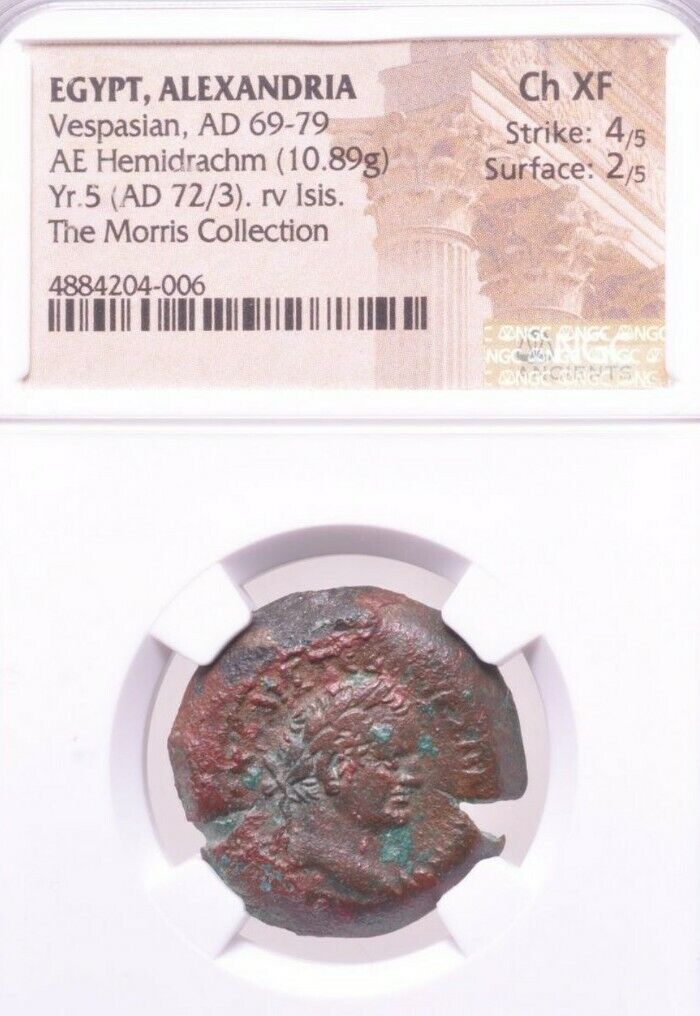

Item:i46698

Authentic Ancient Coin of:

Trajan Decius

-

Roman Emperor

: 249-251 A.D. -

Bronze 'Sestertius' 28mm (18.16 grams) of the province of

Dacia

, struck circa 251 A.D.

Reference: RIC 101b; sear5 #9398; Cohen 22.

IMP CAES C MESS Q DECIO TRAI AVG - laureate, draped and cuirassed bust right

DACIA S-C, Dacia standing left holding draco standard, or staff surmounted by

a donkey's head.

This local era for Dacia begins in 246 AD, the year Philip expelled barbarian invaders from the province.

The lion and the eagle were the emblems of the legions stationed in the province.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

In ancient geography, especially in

Roman

sources,

Dacia

was the land inhabited by the

Dacians

and

Getae

- the North-Danubian branches of the

Thracians

. Dacia had in the middle the

Carpathian Mountains

and was bounded approximately by the

Danubius

river, in Greek sources

Istros

(the

Danube

) or, at its greatest extent, by the

Haemus Mons

(the

Balkan Mountains

) to the south–

Moesia

(

Dobrogea

), a region south of the Danube, was a core area where the Getae lived and interacted with the Ancient Greeks–

Pontus Euxinus

(the

Black Sea

) and river

Danastris

, in Greek sources

Tyras

(the

Dniester

) to the east (but several Dacian settlements are recorded in part of area between Dniester and

Hypanis

river (the

Bug

), and

Tisia

(the

Tisza

) to the west (but at times included areas between Tisza and middle Danube). It thus corresponds to modern countries of

Romania

and

Moldova

, as well as smaller parts of

Bulgaria

,

Serbia

,

Hungary

, and

Ukraine

.

Dacians and Getae were North

Thracian

tribes. Dacian tribes had both peaceful and military encounters with other neighboring tribes, such as

Celts

,

Ancient Germanics

,

Sarmatians

, and

Scythians

, but were most influenced by the Ancient Greeks and

Romans

. The latter eventually conquered, and linguistically and culturally assimilated the Dacians. A Dacian Kingdom of variable size existed between 82 B.C. until the Roman conquest in 106 A.D. The capital of Dacia,

Sarmizegetusa

, located in modern Romania, was destroyed by the Romans, but its name was added to that of the new city (

Ulpia Traiana Sarmizegetusa

) built by the latter to serve as the capital of the

Roman province of Dacia

.

Gaius Messius Quintus Decius

(ca. 201- June 251) was the

Emperor of Rome

from 249 to 251. In the last year of his reign, he co-ruled with his son

Herennius Etruscus

until both of them were killed in the

Battle of Abrittus

.

//

Early life and rise to power

Decius, who was born at

Budalia

, now

Martinci

,

Serbia

near

Sirmium

(

Sremska Mitrovica

), in

Lower Pannonia

was one of the first among a long succession of future Roman Emperors to originate from the provinces of

Illyria

in the Danube. Unlike some of his immediate imperial predecessors such as Philip the Arab or

Maximinus

, Decius was a distinguished senator who had served as

consul

in 232, had been governor of

Moesia

and

Germania Inferior

soon afterwards, served as governor of

Hispania Tarraconensis

between 235-238, and was

urban prefect

of Rome during the early reign of Emperor

Philip the Arab

(Marcus Iulius Phillipus).

Around 245, Emperor Philip entrusted Decius with an important command on the

Danube

. By the end of 248 or 249, Decius was sent to quell the revolt of

Pacatianus

and his troops in Moesia and Pannonia

[3]

; the soldiers were enraged because of the peace treaty signed between Philip and the

Sassanids

. Once arrived, the troops forced Decius to assume the imperial dignity himself instead. Decius still protested his loyalty to Philip, but the latter advanced against him and was killed near

Verona

,

Italy

. The

Senate

then recognized Decius as Emperor, giving him the attribute

Traianus

as a reference to the good emperor

Trajan

. As the Byzantine historian

Zosimus

later noted:

Decius was therefore clothed in purple and forced to undertake the [burdens of] government, despite his reluctance and unwillingness.

Political and monumental initiatives

Decius' political program was focused on the restoration of the strength of the State, both military opposing the external threats, and restoring the public

piety

with a program of renovation of the

State religion

.

Either as a concession to the Senate, or perhaps with the idea of improving public morality, Decius endeavoured to revive the separate office and authority of the

censor

. The choice was left to the Senate, who unanimously selected

Valerian

(afterwards emperor). But Valerian, well aware of the dangers and difficulties attaching to the office at such a time, declined the responsibility. The invasion of the

Goths

and Decius' death put an end to the abortive attempt.

During his reign, he proceeded to construct several building projects in Rome "including the Thermae Deciane or Baths of Decius on the Aventine" which was completed in 252 and still survived through to the

16th century

; Decius also acted to repair the Colosseum, which had been damaged by lightning strikes.

Persecution of Christians

In January 250, Decius issued an edict for the suppression of

Christianity

. The edict itself was fairly clear:

All the inhabitants of the empire were required to sacrifice before the magistrates of their community 'for the safety of the empire' by a certain day (the date would vary from place to place and the order may have been that the sacrifice had to be completed within a specified period after a community received the edict). When they sacrificed they would obtain a certificate (libellus) recording the fact that they had complied with the order.

While Decius himself may have intended the edict as a way to reaffirm his conservative vision of the Pax Romana and to reassure Rome's citizens that the empire was still secure, it nevertheless sparked a "terrible crisis of authority as various [Christian] bishops and their flocks reacted to it in different ways." Measures were first taken demanding that the bishops and officers of the church make a sacrifice for the Emperor, a matter of an oath of allegiance that Christians considered offensive. Certificates were issued to those who satisfied the

pagan

commissioners during the persecution of Christians under Decius. Forty-six such certificates have been published, all dating from 250, four of them from

Oxyrhynchus

. Christian followers who refused to offer a pagan sacrifice for the Emperor and the Empire's well-being by a specified date risked torture and execution. A number of prominent Christians did, in fact, refuse to make a sacrifice and were killed in the process including

Pope Fabian

himself in 250 and "anti-Christian feeling[s] led to pogroms at Carthage and Alexandria." In reality, however, towards the end of the second year of Decius' reign, "the ferocity of the [anti-Christian] persecution had eased off, and the earlier tradition of tolerance had begun to reassert itself." The Christian church though never forgot the reign of Decius whom they labelled as that "fierce tyrant".

At this time, there was a second outbreak of the

Antonine Plague

, which at its height in 251 to 266 took the lives of 5,000 a day in Rome. This outbreak is referred to as the "Plague of

Cyprian

" (the bishop of

Carthage

), where both the plague and the

persecution of Christians

were especially severe. Cyprian's biographer

Pontius

gave a vivid picture of the demoralizing effects of the plague and Cyprian moralized the event in his essay

De mortalitate

. In Carthage the "Decian persecution" unleashed at the onset of the plague sought out Christian scapegoats. Decius' edicts were renewed under Valerius in 253 and repealed under his son,

Gallienus

, in 260-1.

Military actions and death

The

barbarian

incursions into the Empire were becoming more and more daring and frequent whereas the Empire was facing a serious economic crisis in Decius' time. During his brief reign, Decius engaged in important operations against the

Goths

, who crossed the Danube to raid districts of Moesia and

Thrace

. This is the first considerable occasion the Goths — who would later come to play such an important role — appear in the historical record. The Goths under King

Cniva

were surprised by the emperor while besieging

Nicopolis

on the Danube; the Goths fled through the difficult terrain of the

Balkans

, but then doubled back and surprised the Romans near Beroë (modern

Stara Zagora

), sacking their camp and dispersing the Roman troops. It was the first time a Roman emperor fled in the face of Barbarians. The Goths then moved to

Philippopolis

attack

(modern

Plovdiv

), which fell into their hands. The governor of Thrace,

Titus Julius Priscus

, declared himself Emperor under Gothic protection in opposition to Decius but Priscus's challenge was rendered moot when he was killed soon afterwards.

The siege of Philippopolis had so exhausted the numbers and resources of the Goths that they offered to surrender their treasure and prisoners, on condition of being allowed to retire.

[

needed

citation

]

Decius, who had succeeded in surrounding them and hoped to cut off their retreat, refused to entertain their proposals. The final engagement, in which the Goths fought with the courage of despair, under the command of Cniva, took place during the second week of June 251 on swampy ground in the

Ludogorie

(region in northeastern Bulgaria which merges with Dobruja plateau and the Danube Plain to the north) near the small settlement of Abrittus or

Forum Terebronii

(modern

Razgrad

): see

Battle of Abrittus

.

Jordanes

records that Decius' son

Herennius Etruscus

was killed by an arrow early in the battle, and to cheer his men Decius exclaimed, "Let no one mourn; the death of one soldier is not a great loss to the republic." Nevertheless, Decius' army was entangled in the swamp and annihilated in this battle, while he himself was killed on the field of battle. As the historian

Aurelius Victor

relates:

The Decii (ie.

Decius

), while pursuing the barbarians across the Danube, died through treachery at Abrittus after reigning two years....Very many report that the son had fallen in battle while pressing an attack too boldly; that the father however, has strenuously asserted that the loss of one soldier seemed to him too little to matter. And so he resumed the war and died in a similar manner while fighting vigorously.

One literary tradition claims that Decius was betrayed by his successor

Trebonianus Gallus

, who was involved in a secret alliance with the Goths but this cannot be substantiated and was most likely a later invention since Gallus felt compelled to adopt Decius' younger son, Gaius Valens Hostilianus, as joint emperor even though the latter was too young to rule in his own right. It is also unlikely that the shattered Roman legions would proclaim as emperor a traitor who was responsible for the loss of so many soldiers from their ranks. Decius was the first Roman emperor to die in battle against a foreign enemy

The

sestertius

, or

sesterce

, (pl. sestertii) was an

ancient Roman

coin

. During the

Roman Republic

it was a small,

silver

coin issued only on rare occasions. During the

Roman Empire

it was a large

brass

coin.

Helmed Roma head right, IIS behind

Dioscuri

riding right, ROMA in linear frame below. RSC4, C44/7, BMC13.

The name

sestertius

(originally

semis-tertius

) means "2 ½", the coin's original value in

asses

, and is a combination of

semis

"half" and

tertius

"third", that is, "the third half" (0 ½ being

the first half

and 1 ½

the second half

) or "half the third" (two units plus

half the third

unit, or

half

way between the second unit and

the third

). Parallel constructions exist in

Danish

with

halvanden

(1 ½),

halvtredje

(2 ½) and

halvfjerde

(3 ½). The form

sesterce

, derived from

French

, was once used in preference to the Latin form, but is now considered old-fashioned.

It is abbreviated as (originally

IIS

).

Example of a detailed portrait of

Hadrian

117 to 138

History

The sestertius was introduced c. 211 BC as a small

silver

coin valued at one-quarter of a

denarius

(and thus one hundredth of an

aureus

). A silver denarius was supposed to weigh about 4.5 grams, valued at ten grams, with the silver sestertius valued at two and one-half grams. In practice, the coins were usually underweight.

When the denarius was retariffed to sixteen asses (due to the gradual reduction in the size of bronze denominations), the sestertius was accordingly revalued to four asses, still equal to one quarter of a denarius. It was produced sporadically, far less often than the denarius, through 44 BC.

Hostilian

under

Trajan Decius

250 AD

In or about 23 BC, with the coinage reform of

Augustus

, the denomination of sestertius was introduced as the large brass denomination. Augustus tariffed the value of the sestertius as 1/100

Aureus

. The sestertius was produced as the largest

brass

denomination until the late 3rd century AD. Most were struck in the mint of

Rome

but from AD 64 during the reign of

Nero

(AD 54–68) and

Vespasian

(AD 69–79), the mint of

Lyon

(

Lugdunum

), supplemented production. Lyon sestertii can be recognised by a small globe, or legend stop), beneath the bust.

[

citation needed

]

The brass sestertius typically weighs in the region of 25 to 28 grammes, is around 32–34 mm in diameter and about 4 mm thick. The distinction between

bronze

and brass was important to the Romans. Their name for

brass

was

orichalcum

, a word sometimes also spelled

aurichalcum

(echoing the word for a gold coin, aureus), meaning 'gold-copper', because of its shiny, gold-like appearance when the coins were newly struck (see, for example

Pliny the Elder

in his

Natural History

Book 34.4).

Orichalcum

was considered, by weight, to be worth about double that of bronze. This is why the half-sestertius, the

dupondius

, was around the same size and weight as the bronze as, but was worth two asses.

Sestertii continued to be struck until the late 3rd century, although there was a marked deterioration in the quality of the metal used and the striking even though portraiture remained strong. Later emperors increasingly relied on melting down older sestertii, a process which led to the zinc component being gradually lost as it burned off in the high temperatures needed to melt copper (

Zinc

melts at 419 °C,

Copper

at 1085 °C). The shortfall was made up with bronze and even lead. Later sestertii tend to be darker in appearance as a result and are made from more crudely prepared blanks (see the

Hostilian

coin on this page).

The gradual impact of

inflation

caused by

debasement

of the silver currency meant that the purchasing power of the sestertius and smaller denominations like the dupondius and as was steadily reduced. In the 1st century AD, everyday small change was dominated by the dupondius and as, but in the 2nd century, as inflation bit, the sestertius became the dominant small change. In the 3rd century silver coinage contained less and less silver, and more and more copper or bronze. By the 260s and 270s the main unit was the double-denarius, the

antoninianus

, but by then these small coins were almost all bronze. Although these coins were theoretically worth eight sestertii, the average sestertius was worth far more in plain terms of the metal they contained.

Some of the last sestertii were struck by

Aurelian

(270–275 AD). During the end of its issue, when sestertii were reduced in size and quality, the

double sestertius

was issued first by

Trajan Decius

(249–251 AD) and later in large quantity by the ruler of a breakaway regime in the West called

Postumus

(259–268 AD), who often used worn old sestertii to

overstrike

his image and legends on. The double sestertius was distinguished from the sestertius by the

radiate crown

worn by the emperor, a device used to distinguish the dupondius from the as and the antoninianus from the denarius.

Eventually, the inevitable happened. Many sestertii were withdrawn by the state and by forgers, to melt down to make the debased antoninianus, which made inflation worse. In the coinage reforms of the 4th century, the sestertius played no part and passed into history.

Sestertius of

Hadrian

, dupondius of

Antoninus Pius

, and as of

Marcus Aurelius

As a unit of account

The sestertius was also used as a standard unit of account, represented on inscriptions with the monogram HS. Large values were recorded in terms of

sestertium milia

, thousands of sestertii, with the

milia

often omitted and implied. The hyper-wealthy general and politician of the late Roman Republic,

Crassus

(who fought in the war to defeat

Spartacus

), was said by Pliny the Elder to have had 'estates worth 200 million sesterces'.

A loaf of bread cost roughly half a sestertius, and a

sextarius

(~0.5 liter) of

wine

anywhere from less than half to more than 1 sestertius. One

modius

(6.67 kg) of

wheat

in 79 AD

Pompeii

cost 7 sestertii, of

rye

3 sestertii, a bucket 2 sestertii, a tunic 15 sestertii, a donkey 500 sestertii.

Records from

Pompeii

show a

slave

being sold at auction for 6,252 sestertii. A writing tablet from

Londinium

(Roman

London

), dated to c. 75–125 AD, records the sale of a

Gallic

slave girl called Fortunata for 600 denarii, equal to 2,400 sestertii, to a man called Vegetus. It is difficult to make any comparisons with modern coinage or prices, but for most of the 1st century AD the ordinary

legionary

was paid 900 sestertii per annum, rising to 1,200 under

Domitian

(81-96 AD), the equivalent of 3.3 sestertii per day. Half of this was deducted for living costs, leaving the soldier (if he was lucky enough actually to get paid) with about 1.65 sestertii per day.

Perhaps a more useful comparison is a modern salary: in 2010 a private soldier in the US Army (grade E-2) earned about ,000 a year.

Numismatic value

A sestertius of

Nero

, struck at

Rome

in 64 AD. The reverse depicts the emperor on horseback with a companion. The legend reads DECVRSIO, 'a military exercise'. Diameter 35mm

Sestertii are highly valued by

numismatists

, since their large size gave

caelatores

(engravers) a large area in which to produce detailed portraits and reverse types. The most celebrated are those produced for

Neroro

(54-68 AD) between the years 64 and 68 AD, created by some of the most accomplished coin engravers in history. The brutally realistic portraits of this emperor, and the elegant reverse designs, greatly impressed and influenced the artists of the

Renaissance

. The series issued by

Hadrian

(117-138 AD), recording his travels around the Roman Empire, brilliantly depicts the Empire at its height, and included the first representation on a coin of the figure of

Britannia

; it was revived by

Charles II

, and was a feature of

United Kingdom

coinage until the

2008 redesign

.

Very high quality examples can sell for over a million

dollars

at auction as of 2008, but the coins were produced in such colossal abundance that millions survive.

<="" span="">

<="" span="">

<="" span="">

Frequently Asked Questions

How long until my order is shipped?

Depending on the volume of sales, it may take up to 5 business days for shipment of your order after the receipt of payment.

How will I know when the order was shipped?

After your order has shipped, you will be left positive feedback, and that date should be used as a basis of estimating an arrival date.

After you shipped the order, how long will the mail take?

USPS First Class mail takes about 3-5 business days to arrive in the U.S., international shipping times cannot be estimated as they vary from country to country. I am not responsible for any USPS delivery delays, especially for an international package.

What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic?

Each of the items sold here, is provided with a Certificate of Authenticity, and a Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity, issued by a world-renowned numismatic and antique expert that has identified over 10000 ancient coins and has provided them with the same guarantee. You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing.

Compared to other certification companies, the certificate of authenticity is a -50 value. So buy a coin today and own a piece of history, guaranteed.

Is there a money back guarantee?

I offer a 30 day unconditional money back guarantee. I stand behind my coins and would be willing to exchange your order for either store credit towards other coins, or refund, minus shipping expenses, within 30 days from the receipt of your order. My goal is to have the returning customers for a lifetime, and I am so sure in my coins, their authenticity, numismatic value and beauty, I can offer such a guarantee.

Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order?

You can contact me directly via ask seller a question and request my telephone number, or go to my About Me Page to get my contact information only in regards to items purchased on eBay.

When should I leave feedback?

Once you receive your order, please leave a positive. Please don't leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. Also, if you sent an email, make sure to check for my reply in your messages before claiming that you didn't receive a response. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service.