-40%

LEAD TOKEN Helios in LEO Like Antoninus Pius Alexandria Egypt Roman Coin i41621

$ 348.47

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

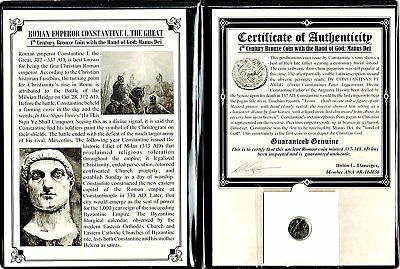

Item:i41621

Authentic Ancient :

Lead Zodiac Leo "Lion" Token

Lead 19mm (5.35 grams) Circa 50-200 A.D.

Lion leaping right; above, radiate and draped bust of Helios; thunderbolt below within incuse countermark.

* Numismatic Note: The the lion looks like reverse type of one of the the Zodiac series coins of Antoninus Pius of Alexandria Egypt. One can explain this type to have been made for the renewal of the Great Sothic cycle, the point when the star Sothis (Sirius) rises on the same point on the horizon as the sun. This cycle of 1461 years began early in the reign of Pius in AD 139, and apparently prompted a renewal in the ancient Egyptian religion.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

The

Sothic cycle

or

Canicular period

is a period of 1,461

ancient Egyptian

years (of 365 days each) or 1,460

Julian

years (averaging 365.25 days each). During a Sothic cycle, the 365-day year loses enough time that the start of the year once again coincides with the

heliacal rising

of the star

Sirius

(the

Latinized

name for

Greek

Σείριος, a star called

Sopdet

by the Egyptians, in Greek transcribed as

Sothis

; a single year between heliacal risings of Sothis is a

Sothic year

). This rising occurred within a month or so of the beginning of the

Nile

flood, and was a matter of primary importance to this

agricultural

society. It is believed that Ancient Egyptians followed both a 365-day civil calendar and a lunar religious calendar.

Mechanics and discovery

The ancient Egyptian civil year was 365 days long, and apparently did not have any

intercalary

days added to keep it in alignment with the Sothic year, a kind of

sidereal year

. Normally, a sidereal year is considered to be 365.25636 days long, but that only applies to stars on the

ecliptic

, or the apparent path of the

Sun

. Because Sirius lies ~40˚ below the ecliptic, the wobbling of the celestial equator and hence of the horizon at the latitude of Egypt, as well as the proper motion of the star, causes the Sothic year to be slightly smaller. Indeed, it is almost exactly 365.25 days long, the average number of days in a Julian year.

This cycle was first noticed by

Eduard Meyer

in 1904, who then carefully combed known Egyptian inscriptions and written materials to find any mention of the calendar dates when Sirius rose. He found six of them, on which the dates of much of the

conventional Egyptian chronology

are based. A heliacal rise of Sirius was recorded by

Censorinus

as having happened on the Egyptian New Year's Day, between AD 139 and 142. The record actually refers to July 21 of 140 AD but is astronomically calculated as a definite July 20 of 139 AD. This correlates the Egyptian calendar to the Julian calendar. Leap day occurs in 140 AD, and so the new year,

Thoth 1

, is July 20 in 139 AD but it is July 19 in 140-142 AD. Thus he was able to compare the day on which Sothis rose in the Egyptian calendar to the day on which Sothis ought to have risen in the Julian calendar, count the number of intercalary days needed, and determine how many years were between the beginning of a cycle and the observation. One also needs to know the place of observation, since the latitude of the observation changes the day when the heliacal rising of Sirius occurs, and mislocating an observation can potentially change the resulting chronology by several decades. Meyer concluded from an ivory tablet from the reign of

Djer

that the Egyptian civil calendar was created in

4241 BC

, a date that appears in a number of old books. But research and discoveries have since shown that the

first dynasty of Egypt

did not begin before c.

3100 BC

, and the claim that 4241 BC (July 19) is the "earliest fixed date" has since been discredited. Most scholars either move the observation upon which he based this forward by one cycle of Sothis to 2781 (July 19), or reject the assumption that the document in question indicates a rise of Sothis at all.

Chronological interpretation

Three specific observations of the heliacal rise of Sirius are extremely important for Egyptian chronology. The first is the aforementioned ivory tablet from the reign of

Djer

which supposedly indicates the beginning of a Sothic cycle, the rising of Sothis on the same day as the new year. If this does indicate the beginning of a Sothic cycle, it must date to about 2773 BC (July 17). However, this date is too late for Djer's reign, so many scholars believe that it indicates a correlation between the rising of Sothis and the lunar calendar, instead of the solar calendar, which would render the tablet essentially devoid of chronological value.

The second observation is clearly a reference to a heliacal rising, and is believed to date to the seventh year of

Senusret III

. This observation was almost certainly made at

Itj-Tawy

, the Twelfth Dynasty capital, which would date the Twelfth Dynasty from 1963 to 1786 BC. The Ramses (Turin) Papyrus Canon says 213 years (1991-1778 BC), Richard Parker reduces it to 206 years (1991-1785 BC), based on July 17 of 1872 BC as the Sothic date (120th year of 12th dynasty, a drift of 30 leap days). Prior to Parker's investigation of lunar dates the 12th dynasty was placed as 213 years of 2007-1794 BC perceiving the date as July 21 of 1888 BC as the 120th year, and then as 2003-1790 BC perceiving the date as July 20 of 1884 BC as the 120th year.

The third observation was in the reign of

Amenhotep I

, and, assuming it was made in Thebes, dates his reign between 1525 and 1504 BC. If made in Memphis, Heliopolis, or some other Delta site instead, as a minority of scholars still argue, the entire chronology of the Eighteenth dynasty needs to be expanded by some 20 years.

Observational Mechanics and Precession

The Sothic cycle is a specific example of two cycles of differing length interacting to cycle together, here called a tertiary cycle. This is mathematically defined by the formula 1/a + 1/b = 1/t or half the harmonic mean. In the case of the Sothic cycle the two cycles are a 365d Egyptian calendar year and a "Sothic" year. Other tertiary cycles occur with turn signals on two different cars, two pumps filling a swimming pool, or the hands on an analog clock passing each other. It is the time required for a faster car to get one lap ahead of a slower car traveling on a race track.

The Sothic year is the length of time for the star Sirius/Sothis to visually return to the same position in relation to the sun. Star years measured in this way vary due to precession, the movement of the Earth's axis in relation to the sun. The length of time for a star to make a yearly path can be marked when it rises to a defined altitude above a local horizon at the time of sunrise. This altitude does not have to be the altitude of first possible visibility. Throughout the year the star will rise approximately four minutes earlier each successive sunrise. Eventually the star will return to its same relative location at sunrise. This length of time can be called an observational year.

Stars that reside close to the ecliptic or the ecliptic meridian will on average exhibit observational years close to the sidereal year of 365.2564d. The ecliptic and the meridian cut the sky into four quadrants. The axis of the earth wobbles around slowly moving the observer and changing the observation of the event. If the axis swings the observer closer to the event its observational year will be shortened. Likewise, the observational year can be lengthened when the axis swings away from the observer. This depends upon which quadrant of the sky the phenomenon is observed.

The Sothic year is remarkable because its average duration was exactly 365.25d in the early 4th millennium BC before the unification of Egypt. The slow rate of change from this value is also of note. If observations and records could have been maintained during predynastic times the Sothic rise would optimally return to the same calendar day after 1461 calendar years. This value would drop to about 1456 calendar years by the Middle Kingdom. The 1461 value could also be maintained if the date of the Sothic rise were artificially maintained by moving the feast in celebration of this event one day every fourth year instead of rarely adjusting it according to observation.

It has been noticed, and the Sothic cycle confirms, that Sirius does not move retrograde across the sky like other stars, a phenomenon widely known as the precession of the equinox. Professor

Jed Buchwald

wrote "Sirius remains about the same distance from the equinoxes – and so from the solstices – throughout these many centuries, despite precession." For the same reason, the helical rising (or zenith) of Sirius does not slip through the calendar (at the precession rate of about one day per 71.6 years), as other stars do. This remarkable stability within the solar year may be one reason that the Egyptians used it as a basis for their calendar whereas no other star would have sufficed.

The lunisolar theory of precession requires that the earth wobble enough to lose one complete rotation on its axis and one revolution around the sun (relative to the fixed stars) per precession cycle. Modern astronomers now measure the rate of precession via radio telescopes fixed on distant quasars and a process known as Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI) confirms the earth changes orientation to the stars at about 50.3 arc seconds per year, equating to one complete precession of the equinox in about 25,700 years. Nonetheless, Sirius, due to its proper motion, remains practically stationary making it the ideal marker for ancient Egyptian planning purposes.

Problems and criticisms

Determining the date of a heliacal rise of Sothis has been shown to be difficult, especially considering the need to know the exact latitude of the observation. Another problem is that because the Egyptian calendar loses one day every four years, a heliacal rise will take place on the same day for four years in a row, and any observation of that rise can date to any of those four years, making the observation not extremely precise.

A number of criticisms have been leveled against the reliability of dating by the Sothic cycle. Some are serious enough to be considered problematic. Firstly, none of the astronomical observations have dates that mention the specific pharaoh in whose reign they were observed, forcing Egyptologists to supply that information on the basis of a certain amount of informed speculation. Secondly there is no information regarding the nature of the civil calendar throughout the course of Egyptian history, forcing Egyptologists to assume that it existed unchanged for thousands of years; the Egyptians would only have needed to carry out one calendar reform in a few thousand years for these calculations to be worthless. Other criticisms are not considered as problematic, e.g. there is no extant mention of the Sothic cycle in ancient Egyptian writing, which may simply be a result of it either being so obvious to Egyptians that it didn't merit mention or to relevant texts being destroyed over time or still awaiting discovery.

Some have recently claimed that the

Theran eruption

marks the beginning of the

Eighteenth dynasty

due to Theran ash and pumice discoveries in the ruins of

Avaris

in layers that mark the end of the Hyksos era

[

citation

needed

]

. Because the evidence of

dendrochronologists

indicates the eruption took place in 1626 BC, this has been taken to indicate that dating by the Sothic cycle is off by 50–80 years at the outset of the 18th dynasty

[

citation

needed

]

. Claims that the Thera eruption is the subject of the

Tempest Stele

of

Ahmose I

have been disputed by writers such as

Peter James

.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long until my order is shipped?

Depending on the volume of sales, it may take up to 5 business days for shipment of your order after the receipt of payment.

How will I know when the order was shipped?

After your order has shipped, you will be left positive feedback, and that date should be used as a basis of estimating an arrival date.

After you shipped the order, how long will the mail take?

USPS First Class mail takes about 3-5 business days to arrive in the U.S., international shipping times cannot be estimated as they vary from country to country. I am not responsible for any USPS delivery delays, especially for an international package.

What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic?

Each of the items sold here, is provided with a Certificate of Authenticity, and a Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity, issued by a world-renowned numismatic and antique expert that has identified over 10000 ancient coins and has provided them with the same guarantee. You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing.

Compared to other certification companies, the certificate of authenticity is a -50 value. So buy a coin today and own a piece of history, guaranteed.

Is there a money back guarantee?

I offer a 30 day unconditional money back guarantee. I stand behind my coins and would be willing to exchange your order for either store credit towards other coins, or refund, minus shipping expenses, within 30 days from the receipt of your order. My goal is to have the returning customers for a lifetime, and I am so sure in my coins, their authenticity, numismatic value and beauty, I can offer such a guarantee.

Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order?

You can contact me directly via ask seller a question and request my telephone number, or go to my About Me Page to get my contact information only in regards to items purchased on eBay.

When should I leave feedback?

Once you receive your order, please leave a positive. Please don't leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. Also, if you sent an email, make sure to check for my reply in your messages before claiming that you didn't receive a response. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service.