-40%

GORDIAN III 238AD Nicaea Bythinia Ancient Roman Coin EAGLE STANDARDS i49388

$ 26.4

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

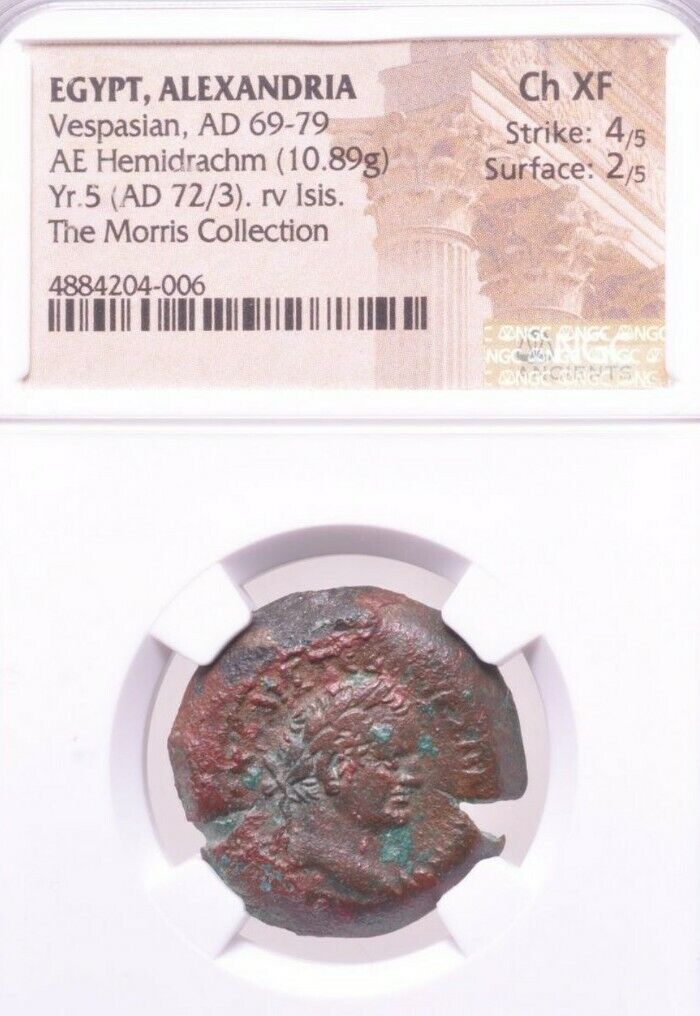

Item:i49388

Authentic Ancient Roman Coin of:

Gordian III -

Roman Emperor

: 238-244 A.D. -

Bronze 19mm (3.73 grams) from the Roman provincial city of Nicaea in the province

of Bythinia 238-244 A.D.

Reference: SNGCop 526, BMC 114, SGI 3671

M ANT ΓOPΔIANOC AV, radiate, draped bust right.

NIKAEΩN, Three legionary standards, centered one tipped with an eagle, the others

with laurel wreaths.

You are bidding on the exact item pictured, provided with a Certificate of Authenticity and Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity.

An

aquila

, or

eagle

, was a prominent symbol used in ancient Rome, especially as the

standard

of a

Roman legion

. A

legionary

known as an

aquilifer

, or eagle-bearer, carried this standard. Each legion carried one eagle.

Roman ornament with an aquila (100–200 AD) from the

Cleveland Museum of Art

.

The eagle was extremely important to the Roman military, beyond merely being a symbol of a legion. A lost standard was considered an extremely grave occurrence, and the Roman military often went to great lengths to both protect a standard and to recover it if lost; for example, see the aftermath of the

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

, where the Romans spent decades attempting to recover the lost standards of three legions.

A modern reconstruction of an

aquila

History

The

signa militaria

were the Roman military

ensigns

or

standards

. The most ancient standard employed by the Romans is said to have been a handful (

manipulus

) of straw fixed to the top of a spear or pole. Hence the company of soldiers belonging to it was called a

maniple

. The bundle of

hay

or

fern

was soon succeeded by the figures of animals, of which

Pliny the Elder

(

H.N.

x.16) enumerates five: the

eagle

, the

wolf

, the ox with the man's head, the

horse

, and the

boar

. In the second consulship of

Gaius Marius

(104 BC) the four quadrupeds were laid aside as standards, the eagle (

Aquila

) alone being retained. It was made of

silver

, or

bronze

, with outstretched wings, but was probably of a relatively small size, since a standard-bearer (

signifer

) under

Julius Caesar

is said in circumstances of danger to have wrenched the eagle from its staff and concealed it in the folds of his girdle.Under the later emperors the eagle was carried, as it had been for many centuries, with the legion, a legion being on that account sometimes called

aquila

(Hirt. Bell. Hisp. 30). Each

cohort

had for its own ensign the

serpent

or

dragon

, which was woven on a square piece of cloth

textilis anguis

, elevated on a

gilt

staff, to which a cross-bar was adapted for the purpose, and carried by the

draconarius

.

Another figure used in the standards was a ball (orb), supposed to have been emblematic of the dominion of Rome over the world; and for the same reason a bronze figure of

Victoria

was sometimes fixed at the top of the staff, as we see it sculptured, together with small statues of Mars, on the

Column of Trajan

and the

Arch of Constantine

. Under the eagle or other emblem was often placed a head of the reigning emperor, which was to the army the object of idolatrous adoration.

[9]

The name of the emperor, or of him who was acknowledged as emperor, was sometimes inscribed in the same situation. The pole used to carry the eagle had at its lower extremity an iron point (cuspis) to fix it in the ground, and to enable the aquilifer in case of need to repel an attack.

The minor divisions of a cohort, called centuries, had also each an ensign, inscribed with the number both of the cohort and of the century. This, together with the diversities of the crests worn by the centurions, enabled each soldier to take his place with ease.

Denarius

minted by

Mark Antony

to pay his legions. On the reverse, the

aquila

of his

Third legion

.

In the

Arch of Constantine

at Rome there are four sculptured panels near the top which exhibit a great number of standards and illustrate some of the forms here described. The first panel represents Trajan giving a king to the Parthians: seven standards are held by the soldiers. The second, containing five standards, represents the performance of the sacrifice called

suovetaurilia

.

When Constantine embraced Christianity, a figure or emblem of Christ, woven in gold upon purple cloth, was substituted for the head of the emperor. This richly ornamented standard was called

labarum

. The labarum is still used today by the

Orthodox Church

in the Sunday service. The entry procession of the chalice whose contents will soon become holy communion is modeled after the procession of the standards of the Roman army.

Eagle and weapons from an

Augustan-era

funerary monument, probably that of

Messalla

(

Prado

,

Madrid

)

Even after the adoption of Christianity as the Roman Empire's religion, the Aquila eagle continued to be used as a symbol. During the reign of

Eastern Roman Emperor

Isaac I Komnenos

, the single-headed eagle was modified to

double-headed

to symbolise the Empire's dominance over

East and West

.

Since the movements of a body of troops and of every portion of it were regulated by the standards, all the evolutions, acts, and incidents of the Roman army were expressed by phrases derived from this circumstance. Thus

signa inferre

meant to advance,

[15]

referre

to retreat, and

convertere

to face about;

efferre

, or

castris vellere

, to march out of the camp;

ad signa convenire

, to re-assemble. Notwithstanding some obscurity in the use of terms, it appears that, whilst the standard of the legion was properly called

aquila

, those of the cohorts were in a special sense of the term called

signa

, their bearers being

signiferi

, and that those of the manipuli or smaller divisions of the cohort were denominated

vexilla

, their bearers being

vexillarii

. Also, those who fought in the first ranks of the legion before the standards of the legion and cohorts were called

antesignani

.

In military stratagems it was sometimes necessary to conceal the standards. Although the Romans commonly considered it a point of honour to preserve their standards, in some cases of extreme danger the leader himself threw them among the ranks of the enemy in order to divert their attention or to animate his own soldiers. A wounded or dying standard-bearer delivered it, if possible, into the hands of his general, from whom he had received it

signis acceptis

.

Lost

Aquilae

Battles where the Aquilae were lost, units that lost the Aquilae and the fate of the Aquilae:

53 BC -

Battle of Carrhae

. Crassus

Legio X

(returned).

40 BC - defeat of

Decidius Saxa

at

Cilicia

(returned).

36 BC - defeat of

Mark Antony

(returned).

19 BC -

Cantabrian Wars

at Hispania.

Legio I Germanica

(thought to have been lost, and stripped of its title "Augusta").

9 AD -

Battle of the Teutoburg Forest

.

Legio XVII

,

Legio XVIII

, and

Legio XIX

(all recaptured).

66 -

Great Jewish Revolt

.

Legio XII Fulminata

(fate uncertain).

87 -

Domitian's Dacian War

.

Legio V Alaudae

(fate uncertain).

132 -

Bar Kochva Revolt

.

Legio XXII Deiotariana

(fate uncertain).

161 - Parthians overrun a legion commanded by Severianus at Elegeia in Armenia, possibly the

Ninth Legion

.

[23]

Modern imagery

Reconstruction of

aquila

on Roman vexilloid

Aquila

clutching fasces, a symbol in Italy during the Fascist period

Aquila

on the

coat of arms of Romania

Standards

Roman military standards. The standards with discs, or

signa

(

first three on left

) belong to

centuriae

of the legion (the image does not show the heads of the standards - whether spear-head or wreathed-palm). Note (

second from right

) the legion's

aquila

. The standard on the extreme right probably portrays the

She-wolf

(

lupa

) which fed

Romulus

, the legendary founder of Rome. (This was the emblem of

Legio VI Ferrata

, a legion then based in

Judaea

, a detachment of which is known to have fought in Dacia). Detail from Trajan's Column, Rome

Modern reenactors parade with replicas of various legionary standards. From left to right:

signum

(spear-head type), with four discs;

signum

(wreathed-palm type), with six discs;

imago

of ruling emperor; legionary

aquila

;

vexillum

of commander (

legatus

) of

Legio XXX Ulpia Victrix

, with embroidered name and emblem (

Capricorn

) of legion

Each tactical unit in the imperial army, from

centuria

upwards, had its own standard. This consisted of a pole with a variety of adornments that was borne by dedicated standard-bearers who normally held the rank of

duplicarius

. Military standards had the practical use of communicating to unit members where the main body of the unit was situated, so that they would not be separated, in the same way that modern tour-group guides use umbrellas or flags. But military standards were also invested with a mystical quality, representing the divine spirit (

genius

) of the unit and were revered as such (soldiers frequently prayed before their standards). The loss of a unit's standard to the enemy was considered a terrible stain on the unit's honour, which could only be fully expunged by its recovery.

The standard of a

centuria

was known as a

signum

, which was borne by the unit's

signifer

. It consisted of a pole topped by either an open palm of a human hand or by a spear-head. The open palm, it has been suggested, originated as a symbol of the

maniple

(

manipulus

= "handful"), the smallest tactical unit in the

Roman army of the mid-Republic

. The poles were adorned with two to six silver discs (the significance of which is uncertain). In addition, the pole would be adorned by a variety of cross-pieces (including, at bottom, a crescent-moon symbol and a tassel). The standard would also normally sport a cross-bar with tassels.

The standard of a Praetorian cohort or an auxiliary cohort or

ala

was known as a

vexillum

or banner. This was a square flag, normally red in colour, hanging from a crossbar on the top of the pole. Stitched on the flag would be the name of the unit and/or an image of a god. An exemplar found in Egypt bears an image of the goddess Victory on a red background. The

vexillum

was borne by a

vexillarius

. A legionary detachment (

vexillatio

) would also have its own

vexillum

. Finally, a

vexillum

traditionally marked the commander's position on the battlefield.

[194]

The exception to the red colour appears to have been the Praetorian Guard, whose

vexilla

, similar to their clothing, favoured a blue background.

From the time of

Marius

(consul 107 BC), the standard of all legions was the

aquila

("eagle"). The pole was surmounted by a sculpted eagle of solid gold, or at least gold-plated silver, carrying thunderbolts in its claws (representing

Jupiter

, the highest Roman god. Otherwise the pole was unadorned. No exemplar of a legionary eagle has ever been found (doubtless because any found in later centuries were melted down for their gold content). The eagle was borne by the

aquilifer

, the legion's most senior standard-bearer. So important were legionary eagles as symbols of Roman military prestige and power, that the imperial government would go to extraordinary lengths to recover those captured by the enemy. This would include launching full-scale invasions of the enemy's territory, sometimes decades after the eagles had been lost e.g. the expedition in 28 BC by

Marcus Licinius Crassus

against

Genucla

(Isaccea, near modern

Tulcea

, Rom., in the Danube delta region), a fortress of the

Getae

, to recover standards lost 33 years earlier by

Gaius Antonius

, an earlier

proconsul

of

Macedonia

. Or the campaigns of AD 14-17 to recover the three eagles lost by

Varus

in AD 6 in the

Teutoburg Forest

.

Under Augustus, it became the practice for legions to carry portraits (

imagines

) of the ruling emperor and his immediate family members. An

imago

was usually a bronze bust carried on top of a pole like a standard by an

imaginifer

.

From around the time of Hadrian (r. 117-38), some auxiliary

alae

adopted the dragon-standard (

draco

) commonly carried by Sarmatian cavalry squadrons. This was a long cloth wind-sock attached to an ornate sculpture of an open dragon's mouth. When the bearer (

draconarius

) was galloping, it would make a strong hissing-sound.

Decorations

The Roman army awarded a variety of individual decorations (

dona

) for valour to its legionaries.

Hasta pura

was a miniature spear;

phalerae

were large medal-like bronze or silver discs worn on the cuirass;

armillae

were bracelets worn on the wrist; and

torques

were worn round the neck, or on the cuirass. The highest awards were the

coronae

("crowns"), of which the most prestigious was the

corona civica

, a crown made oak-leaves awarded for saving the life of a fellow Roman citizen in battle. The most valuable award was the

corona muralis

, a crown made of gold awarded to the first man to scale an enemy rampart. This was awarded rarely, as such a man hardly ever survived.

There is no evidence that auxiliary common soldiers received individual decorations like legionaries, although auxiliary officers did. Instead, the whole regiment was honoured by a title reflecting the type of award e.g.

torquata

("awarded a torque") or

armillata

("awarded bracelets"). Some regiments would, in the course of time, accumulate a long list of titles and decorations e.g.

cohors I Brittonum Ulpia torquata pia fidelis c.R.

.

Nicaea

Early history, Roman and Byzantine Empires

The place is said to have been colonized by

Bottiaeans

, and to have originally borne the name of

Ancore

(

Steph. B.

s. v.) or

Helicore

(Geogr. Min. p. 40, ed. Hudson); but it was subsequently destroyed by the

Mysians

. A few years after the death of

Alexander the Great

,

Macedonian

king

Antigonus

— who had taken control of much of

Asia Minor

upon the death of Alexander (under whom Antigonus had served as a general) — probably after his victory over

Eumenes

, in 316 BC, rebuilt the town, and called it, after himself,

Antigoneia

(

Greek

:

Αντιγόνεια

). (Steph. B. l. c.; Eustath. ad Horn. II. ii. 863) Several other of Alexander's generals (known together as the

Diadochi

(Latin; original Greek

Diadokhoi

Διάδοχοι/

"successors")) later conspired to remove Antigonus, and after defeating him the area was given to

Thessalian

general

Lysimachus

(

Lysimakhos

) (circa 355 BC-281 BC) in 301 BC as his share of the lands. He renamed it

Nicaea

(Greek:

Νίκαια

, also

transliterated

as

Nikaia

or

Nicæa

; see also

List of traditional Greek place names

), in tribute to his wife Nicaea, a daughter of

Antipater

. (Steph. B., Eustath., Strab., ll. cc.) According to another account (Memnon, ap. Phot. Cod. 224. p. 233, ed. Bekker), Nicaea was founded by men from

Nicaea

near

Thermopylae

, who had served in the army of Alexander the Great. The town was built with great regularity, in the form of a square, measuring 16 stadia in circumference; it had four gates, and all its streets intersected one another at right angles, so that from a monument in the centre all the four gates could be seen. (

Strabo

xii. pp. 565

et seq.

) This monument stood in the gymnasium, which was destroyed by fire, but was restored with increased magnificence by the

younger Pliny

(Epist. x. 48), when he was governor of

Bithynia

.

The city was built on an important crossroads between

Galatia

and

Phrygia

, and thus saw steady trade. Soon after the time of Lysimachus, Nicaea became a city of great importance, and the kings of Bithynia, whose era begins in 288 BC with

Zipoetes

, often resided at Nicaea. It has already been mentioned that in the time of Strabo it is called the metropolis of Bithynia, an honour which is also assigned to it on some coins, though in later times it was enjoyed by

Nicomedia

. The two cities, in fact, kept up a long and vehement dispute about the precedence, and the 38th oration of

Dio Chrysostomus

was expressly composed to settle the dispute. From this oration, it appears that Nicomedia alone had a right to the title of metropolis, but both were the first cities of the country.

The younger Pliny makes frequent mention of Nicaea and its public buildings, which he undertook to restore when governor of Bithynia. (Epist. x. 40, 48, etc.) It was the birthplace of the astronomer

Hipparchus

(ca. 194 BC), the mathematician and astronomer

Sporus

(ca. 240) and the historian

Dio Cassius

(ca. 165).

[1]

It was the death-place of the comedian

Philistion

. The numerous coins of Nicaea which still exist attest the interest taken in the city by the emperors, as well as its attachment to the rulers; many of them commemorate great festivals celebrated there in honour of gods and emperors, as Olympia, Isthmia, Dionysia, Pythia, Commodia, Severia, Philadelphia, etc. Throughout the imperial period, Nicaea remained an important town; for its situation was particularly favourable, being only 40 km (25 mi) distant from

Prusa

(

Pliny

v. 32), and 70 km (43 mi) from

Constantinople

. (

It. Ant.

p. 141.) When Constantinople became the capital of the

Eastern Empire

, Nicaea did not lose in importance; for its present walls, which were erected during the last period of the Empire, enclose a much greater space than that ascribed to the place in the time of Strabo. Much of the existing architecture and defensive works date to this time, early 300s.

Nicaea suffered much from earthquakes in 358, 362 and 368; after the last of which, it was restored by the emperor

Valens

. During the Middle Ages it was for a long time a strong bulwark of the

Byzantine

emperors against the

Turks

.

Nicaea in early Christianity

In the reign of

Constantine

, 325, the celebrated

First Council of Nicaea

was held there against the

Arian

heresy

, and the prelates there defined more clearly the concept of the

Trinity

and drew up the

Nicene Creed

. The

doctrine

of the Trinity was finalized at the Council of Constantinople in 381 AD which expressly included the Holy Ghost as equal to the Father and the Son. The first Nicene Council was probably held in what would become the now ruined mosque of Orchan. The church of Hagia Sophia was built by

Justinian I

in the middle of the city in the 6th century (modelled after the larger

Hagia Sophia

in Constantinople), and it was there that the

Second Council of Nicaea

met in 787 to discuss the issues of

iconography

.

Marcus Antonius Gordianus Pius

(

January 20

,

225

–

February 11

,

244

), known in

English

as

Gordian III

,

was

Roman Emperor

from 238 to 244. Gordian was the son of

Antonia Gordiana

and his father was an unnamed Roman Senator who died before 238. Antonia Gordiana was the daughter of Emperor

Gordian I

and younger sister of Emperor

Gordian II

. Very little is known on his early life before becoming Roman Emperor. Gordian had assumed the name of his maternal grandfather in 238.

Rise to power

Following the murder of emperor

Alexander Severus

in Moguntiacum (modern

Mainz

), the capital of the

Roman province

Germania Inferior

,

Maximinus Thrax

was acclaimed emperor, despite strong opposition of the

Roman senate

and the majority of the population. In response to what was considered in Rome as a rebellion, Gordian's grandfather and uncle, Gordian I and II, were proclaimed joint emperors in the

Africa Province

. Their revolt was suppressed within a month by Cappellianus, governor of

Numidia

and a loyal supporter of Maximinus Thrax. The elder Gordians died, but public opinion cherished their memory as peace loving and literate men, victims of Maximinus' oppression.

Meanwhile, Maximinus was on the verge of marching on Rome and the Senate elected

Pupienus

and

Balbinus

as joint emperors. These senators were not popular men and the population of Rome was still shocked by the elder Gordian's fate, so that the Senate decided to take the teenager Gordian, rename him Marcus Antonius Gordianus as his grandfather, and raise him to the rank of

Caesar

and imperial heir.

Pupienus

and

Balbinus

defeated Maximinus, mainly due to the defection of several

legions

, namely the

Parthica

II

who assassinated Maximinus. But their joint reign was doomed from the start with popular riots, military discontent and even an enormous fire that consumed Rome in June 238. On

July 29

, Pupienus and Balbinus were killed by the

Praetorian guard

and Gordian proclaimed sole emperor.

Rule

Due to Gordian's age, the imperial government was surrendered to the aristocratic families, who controlled the affairs of Rome through the senate. In 240,

Sabinianus

revolted in the African province, but the situation was dealt quickly. In 241, Gordian was married to Furia Sabinia

Tranquillina

, daughter of the newly appointed praetorian prefect,

Timesitheus

. As chief of the Praetorian guard and father in law of the emperor, Timesitheus quickly became the

de facto

ruler of the Roman empire.

In the 3rd century, the Roman frontiers weakened against the Germanic tribes across the

Rhine

and

Danube

, and the

Sassanid

kingdom across the

Euphrates

increased its own attacks. When the Persians under

Shapur I

invaded

Mesopotamia

, the young emperor opened the doors of the

Temple of Janus

for the last time in Roman history, and sent a huge army to the East. The Sassanids were driven back over the Euphrates and defeated in the

Battle of Resaena

(243). The campaign was a success and Gordian, who had joined the army, was planning an invasion of the enemy's territory, when his father-in-law died in unclear circumstances. Without Timesitheus, the campaign, and the emperor's security, were at risk.

Year of the Six Emperors

-

238

Maximinus Thrax

Gordian I

and

Gordian II

Pupienus

and

Balbinus

, nominally with

Gordian III

Gordian III

Marcus Julius Philippus, also known as

Philip the Arab

, stepped in at this moment as the new Praetorian Prefect and the campaign proceeded. In the beginning of 244, the Persians counter-attacked. Persian sources claim that a battle was fought (

Battle of Misiche

) near modern

Fallujah

(

Iraq

) and resulted in a major Roman defeat and the death of Gordian III

[1]

. Roman sources do not mention this battle and suggest that Gordian died far away, upstream of the Euphrates. Although ancient sources often described Philip, who succeeded Gordian as emperor, as having murdered Gordian at Zaitha (Qalat es Salihiyah), the cause of Gordian's death is unknown.

Gordian's youth and good nature, along with the deaths of his grandfather and uncle and his own tragic fate at the hands of another usurper, granted him the everlasting esteem of the Romans. Despite the opposition of the new emperor, Gordian was deified by the Senate after his death, in order to appease the population and avoid riots.

Frequently Asked Questions

How long until my order is shipped?:

Depending on the volume of sales, it may take up to 5 business days for shipment of your order after the receipt of payment.

How will I know when the order was shipped?:

After your order has shipped, you will be left positive feedback, and that date should be used as a basis of estimating an arrival date.

After you shipped the order, how long will the mail take?

USPS First Class mail takes about 3-5 business days to arrive in the U.S., international shipping times cannot be estimated as they vary from country to country. I am not responsible for any USPS delivery delays, especially for an international package.

What is a certificate of authenticity and what guarantees do you give that the item is authentic?

Each of the items sold here, is provided with a Certificate of Authenticity, and a Lifetime Guarantee of Authenticity, issued by a world-renowned numismatic and antique expert that has identified over 10000 ancient coins and has provided them with the same guarantee. You will be quite happy with what you get with the COA; a professional presentation of the coin, with all of the relevant information and a picture of the coin you saw in the listing.

Compared to other certification companies, the certificate of authenticity is a -50 value. So buy a coin today and own a piece of history, guaranteed.

Is there a money back guarantee?

I offer a 30 day unconditional money back guarantee. I stand behind my coins and would be willing to exchange your order for either store credit towards other coins, or refund, minus shipping expenses, within 30 days from the receipt of your order. My goal is to have the returning customers for a lifetime, and I am so sure in my coins, their authenticity, numismatic value and beauty, I can offer such a guarantee.

Is there a number I can call you with questions about my order?

You can contact me directly via ask seller a question and request my telephone number, or go to my About Me Page to get my contact information only in regards to items purchased on eBay.

When should I leave feedback?

Once you receive your order, please leave a positive. Please don't leave any negative feedbacks, as it happens many times that people rush to leave feedback before letting sufficient time for the order to arrive. Also, if you sent an email, make sure to check for my reply in your messages before claiming that you didn't receive a response. The matter of fact is that any issues can be resolved, as reputation is most important to me. My goal is to provide superior products and quality of service.